I'm a terrible reader. A disgustingly lackadaisical consumer of the written word- I skim, skip and subliminally abbreviate and summarise reams of text day in day out. Yet I actually read, I mean properly read, wallow in words, slather my brain in sentences, very very rarely. I honestly can't remember the last novel, or any long form book for that matter, that I read through, cover to cover, before July. I have had excuses- too busy, books are heavy and I try and keep the weight of my backpack down, too tired, but there's been no such defence of late. So I have read, and I have loved it.

The State We're In by Will Hutton (1996 edition)

I've long been a fan of Hutton, and caught him at a fascinating book signing in Cambridge perhaps nine years ago, when touring The World We're In. Brilliant and engaging speaker and lucid writer though he may be, I have to confess I didn't have the stomach to dive into this book, an in depth analysis of Britain's social and economic structural malaise written in the dog days of the Major government. It really was one those I thought I'd get around to eventually, and I'm glad I did, because at the dawn of another Tory fiasco it's salutary to be reminder just how wrong this bunch can get it, and to have the failed promises of the New Labour dream held up for review.

I hope the opposition front bench have taken the time to re-appraise this seminal work's impact- so many of them helped the author in the preparation of the work. Now is the perfect time to look back and see how this piercing insight and careful prescription for the way ahead was squandered, and how next time they'll need to do so much better. He predicts the banking crisis perfectly by the way, and also warns against exactly the policy line taken by Brown with the bankers. Reading this reminds me that Britain could have had a Jed Bartlett, instead of the lightweight Blair and belligerent Brown.

Surface Detail by Iain M Banks on Kindle

I do love a decent Culture book, and this is a decent culture book. Not perhaps the shocking apogee of the genre ( Phlebas?), but better than the Algebraist (that somehow just didn't click) but with nicely rounded characters human and AI this had enough of a bouncing plot to keep me happy. Part of me doesn't want to review in too much detail, because it did feel light in all honesty, in spite of the subject matter (hell itself, or rather the construction of artificial hells) and there have been more artfully crafted moral and philosophical dilemmas in this sequence of works. What I will mention is the experience of reading on a Kindle- I bought one as a thank you to Rowan for all the help and support she has given me these past few months. Somehow the fates conspired such that she had no time to use it, so I availed myself of its e-ink charms.

I found the experience to be mixed to be honest. On the positive side it is very convenient. Although the browsing experience is a bit clunky and somehow the online catalogue available feels limited compared to Amazon's own website, it is quick and easy to find stuff you want. Getting books onto the device is very easy too. The screen is clear and easy on the eye, the navigation within the book is fine. It's light, lasts forever on battery, and very convenient.

However, it's not perfect, and it certainly not 'delightful', which certainly some device manufacturers and online experience designers aim for. It's a grim dark matte grey colour of the device body for one thing, with a gritty plasticy texture and some snaggy edges. The buttons feel cheap and plasticy and stiff, the design of the 'forward' and 'back' controls feels compromised and cludged and un-natural, and on screen navigation is awkward. And though the screen itself is clear, and sharp and usable, the shades of dark charcoal text on dreary light grey background are very cold to the eye. Functional, effective and usable, but in no way delightful.

Worst of all though I don't now have a copy of the book on a shelf, well thumbed and creased at the best bits, to remind me of reading it and to colour the space around me. Oh,and I couldn't read it in the bath because it's not waterproof and ok, books aren't either, but a book is cheaper than a Kindle.

The Debt to Pleasure by John Lanchester

I actually started on this one a few years ago and somehow put it down and then didn't pick it up. Not bored with it, just lost track. Lanchester's work has great variety- Mr Phillips and Fragrant Harbour are both great novels very different in style and subject, but this book is probably a standout. I'm being very unfair, but it's rather like a crime caper featuring the arch offspring of Brian Sewell and the galloping gourmet. A very upsettingly funny book.

Our Cosmic Habitat by Sir Martin Rees

I think Rowan bought this for me after we saw Sir Martin speak at Hay on Wye some years ago. That was an interesting if necessarily light discussion of the challenges and insights of cosmology and astronomy, but in this work he introduces some truely mind bending ideas about the incredible circumstances of our place in the known universe. I'm generally comfortable with a materialist atheistic view of us as fortunate pond scum on an unremarkable ball of rock in a quite corner of a thoroughly average galaxy in a completely ordinary corner of the universe, but Rees here makes clear how extraordinarily peculiar the substance of that universe really is. This isn't to at all challenge the idea that nature is what it is, and we're just plopped down into it at all- there's certainly no logical train that goes from an unexpectedly anthropocentric universe to a universal conscious design or intelligent creator, because it's not anthopocentric. However, it is profoundly unsettling to grapple with the undeniable conclusions of rigorous observations that make clear that you, me and everyone we know, and the whole world, the sun, the moon the planets and every star in the sky, are made of stuff, matter, that is on the great scheme of things, just fluff in the gearbox of the great forces that make the universe the way it is, was, and shall be. The charm of this book is that Sir Martin makes this all crystal clear in such an overwhelmingly civilised and urbane way. I shall be reading more of his stuff, I recommend you do too.

The Man Who Changed Everything by Basil Mahon

Maxwell has facinated me for years, ever since I saw the Maxwell building at the University of Salford. "Why name a building after a brand of vile coffee?" I asked my grandfather. This was long before I heard of Captain Bob you understand. "Maxwell" I was told by my radar engineer Grandfather "was one of the cleverest men that ever lived, and he discovered how radio, electric and magnetic forces were related". Electric principles always pushed the very limit of my intellect at school, not helped by a sequence of maths and physics teachers who were unable or unwilling to help me find my own mental model of what was occuring, so I continued to see Maxwell in awe, reinforced when reading such bon mots as Feynman's statement that From a long view of the history of mankind — seen from, say, ten thousand years from now, there can be little doubt that the most significant event of the 19th century will be judged as Maxwell's discovery of the laws of electrodynamics. The American Civil War will pale into provincial insignificance in comparison with this important scientific event of the same decade.

I like science biographies, and Mahon's book promised something else besides the biographical- as an engineer himself, Mahon would hopefully be able to give some sensible context to Maxwell's life and work, showing how the ideas related to earlier concepts, and fitted into an age of burgeoning scientific advance. This isn't always the case- too often I find that historical biographies of great thinkers will tell a cracking story of their life, and even go into facinating detail about their relationships with other thinkers, but will leave one rather wondering what all the fuss was about and having no clear idea what the person did. Lisa Jardine being a particularly strident example of this sort of work. It's ok for architects and artists and politicians, but a scientist engineer or philosopher must be described in terms of their work by somebody prepared to grapple with the barest elements of that work.

In Mahon's work the fecundity and brilliance of Maxwell is made clear, as is his dependence upon and influence over a vast army of scientists and engineers across the world. And even better, by exploring the development of Maxwell's ideas step by step, one is introduced to that most incredible of intellectual leaps, the full abstraction to mathematics of electrodynamics. It's a desperately hard leap to take, and I can only assume some people are so equipped intellectually to 'take flight' into it naturally without a second though, but most will be left behind- floundering with the essential questions "but why? how? what does it mean?". Mahon shows how Maxwell thought through to this eventual, stunning, powerful and revolutionary idea in difficult, but traceable steps. This is like reading a great book with maps of how an unassailable peak was conquered, and has al the exhilaration attendant with such feats of exploration and adventure. Another cracker.

Tomorrow I go under the knife, and rather than killing time, I shall be from then on striving to return to a level of health and fitness I have not attained for a decade or more. Reading will once again have to be 'fitted in'. Recommendations welcome.

This is the blog of Ant Miller, senior research manager and dilettante geek at large at the BBC.

I wail moan and cuss about the challenges and fun to be found here.

These are my personal opinions, and not those of my employer. Or anyone else here for that matter.

I wail moan and cuss about the challenges and fun to be found here.

These are my personal opinions, and not those of my employer. Or anyone else here for that matter.

Sunday, September 18, 2011

Thursday, September 15, 2011

Review of "Medal of Honor" PS3 Game: Gameplay and Historiography

This is an edited verion of my review of the Medal of Honor game on Amazon.co.uk.

MoH is a great game for the PS3- not without it's shortcomings, but none the less a superbly playable and engaging entertainment. It's also an interesting object lesson in the way that popular entertainment and history are renegotiating their relationship in the early years of the 21st century.

As a game I'm going to focus on the single player campaign mode. MoH has 3 main game modes- campaign, onslaught (a variation on campaign where there are no 'saves' and your performance is ranked online) and multiplayer. This last was actually developed seperately to the campaign, and falls somewhere between the Battlefield approach of highly tactical cooperation, and the CoD 'kill/die/spawn' twitch fest (not my cup of tea).

The campaign is basically a fictionalised account of 3 days of activities by US special forces in southern Afghanistan in 2001 and 2002. The history I shall come too, but in essence the developers have taken a few 'set piece' battles and events, and woven them into a compelling and nail biting sequence of missions. The pace is delightfully varied, from stealthy creeping work, to desperate all guns blazing last stands, and the added variety of some lovely vehicle levels. I never really got the hand of the quad bikes, but they're just for transport between levels. On the other hand, the Apache gunship level is simply delightful- in spite of being a pretty standard 'on rails' shooter level there's almost no feeling of being constrained. All the levels have a real feeling of challenge- the few I made it through without respawning to a save felt like I'd scraped in by the skin of my teeth, and in most I had to retry tactics and approaches. There's certainly more than one way to skin a cat in this game, but an almost infinite number of ways for the cat to skin you!

On the down side- I finished this in an afternoon- maybe 5 hours of play, 3.5 hours of actual game time (restarts etc). Some levels could perhaps have been eeked out a little more (the taking of Bagram airfield felt abbreviated somehow) but then again, perhaps that's where the difficulty comes in (I played through on the medium level). The multiplayer has some great maps but as a noob you really are chum to the sharks when you join. And the lack of a squad mechanic feels peculiar, when the single player is carried through in a totally squad level story.

In fact this lack of any squad mechanic in the game is the single biggest weakness overall. The characters you play are all mid to low level ranks on the field, there's always a sergeant, a CPO or someone else to give the orders. Sure, that's a nice way to get hints into the game, keep is relatively simple, but it does set a 'headroom' for what you can do, how much charge one can take, and leaves one feeling ever so slightly that one is 'along for the ride'.

But it is quite a ride- a fictionalised account of the very real, crucial, controversial and harrowing experiences of US special forces in the early days of the latest Afghan War. In these early days of the conflict US, UK, Australian and other coalition special forces worked alongside the 'Nothern Alliance' of tribes to oust the Taliban government of Afghanistan, and then put the pressure on al Qaeda's forces in the south east, along the Pakistan border. this game opens with a couple of mission looking at the initial fight against the Taliban, including the taking of Bagram airbase. Slightly annoying to a British game player and reviewer this operation was historically conducted by a UK SBS team, not US Seals as the game portrays. And here the fictionalisation begins!

We then move forward a few months, into Operation Anaconda- or more specifically the brief mountain top Battle of Takur Ghar- the infamous assault on the Taliban in the Shahi-Kot valley. Here the developers have taken known elements- special forces teams being dropped into hot LZs, teams being split up, downed transport helicopters, and spritzed the whole up with an archetypal 'idiot boss' general back in the the US (though not in uniform, and not in Washington apparently). This is probably the account of the operation that most people will have seen- 5 million copies of this game have been sold. Many more than would have read an in depth report of the battle, or watched in full any of the news reports (which at the time omitted many of the details for operational security reasons, and probably more than a little embarrassment on the part of the Nato forces). So, when we see US forces subduing a goat-herd by rendering him unconscious, it is in contrast to the reports that US forces criticised German special forces for not killing such by standers. The developers have civilised the US forces. And when the Apaches level a village (a LOT of fun it has to be said) we are told there are no civilians there at all, again in contrast to reported actuality.

This is bowlderised Hollywood historical revisionism of a peculiarly insidious kind. Perhaps. The US is seen as being the sole protagonist nation (UK, Australian, Norwegian, & German forces who are a critical part of the historical event are completely airbrushed out). US forces are shown to treat civilians dubiously, but not murderously as the historical record suggests. Mistakes in planning and deployment are scapegoated onto a single distant general, rather than being the result of complex institutional failures. And the tragedy of lone soldiers and operators being abandoned on mountainsides to be killed alone is replaced by a heroic, if ultimately [SPOILERS!] tale of teams sticking together through thick and thin.

It is just a game, and as I have said early, a pretty good one at that. But this is 'popular history' now. This is the 'Longest Day' of our age, the 'Bridge Over the River Kwai' of the Afghan War. We're seeing a few books, but this, to US eyes at least, second division scrap isn't even getting the meager cultural sifting that that war received. It's a dark and shadowed war, and if this is the only light cast on it, then I fear for history today.

MoH is a great game for the PS3- not without it's shortcomings, but none the less a superbly playable and engaging entertainment. It's also an interesting object lesson in the way that popular entertainment and history are renegotiating their relationship in the early years of the 21st century.

|

| Cover art for Medal of Honor EU release. Copyright Electronic Arts |

The campaign is basically a fictionalised account of 3 days of activities by US special forces in southern Afghanistan in 2001 and 2002. The history I shall come too, but in essence the developers have taken a few 'set piece' battles and events, and woven them into a compelling and nail biting sequence of missions. The pace is delightfully varied, from stealthy creeping work, to desperate all guns blazing last stands, and the added variety of some lovely vehicle levels. I never really got the hand of the quad bikes, but they're just for transport between levels. On the other hand, the Apache gunship level is simply delightful- in spite of being a pretty standard 'on rails' shooter level there's almost no feeling of being constrained. All the levels have a real feeling of challenge- the few I made it through without respawning to a save felt like I'd scraped in by the skin of my teeth, and in most I had to retry tactics and approaches. There's certainly more than one way to skin a cat in this game, but an almost infinite number of ways for the cat to skin you!

On the down side- I finished this in an afternoon- maybe 5 hours of play, 3.5 hours of actual game time (restarts etc). Some levels could perhaps have been eeked out a little more (the taking of Bagram airfield felt abbreviated somehow) but then again, perhaps that's where the difficulty comes in (I played through on the medium level). The multiplayer has some great maps but as a noob you really are chum to the sharks when you join. And the lack of a squad mechanic feels peculiar, when the single player is carried through in a totally squad level story.

In fact this lack of any squad mechanic in the game is the single biggest weakness overall. The characters you play are all mid to low level ranks on the field, there's always a sergeant, a CPO or someone else to give the orders. Sure, that's a nice way to get hints into the game, keep is relatively simple, but it does set a 'headroom' for what you can do, how much charge one can take, and leaves one feeling ever so slightly that one is 'along for the ride'.

But it is quite a ride- a fictionalised account of the very real, crucial, controversial and harrowing experiences of US special forces in the early days of the latest Afghan War. In these early days of the conflict US, UK, Australian and other coalition special forces worked alongside the 'Nothern Alliance' of tribes to oust the Taliban government of Afghanistan, and then put the pressure on al Qaeda's forces in the south east, along the Pakistan border. this game opens with a couple of mission looking at the initial fight against the Taliban, including the taking of Bagram airbase. Slightly annoying to a British game player and reviewer this operation was historically conducted by a UK SBS team, not US Seals as the game portrays. And here the fictionalisation begins!

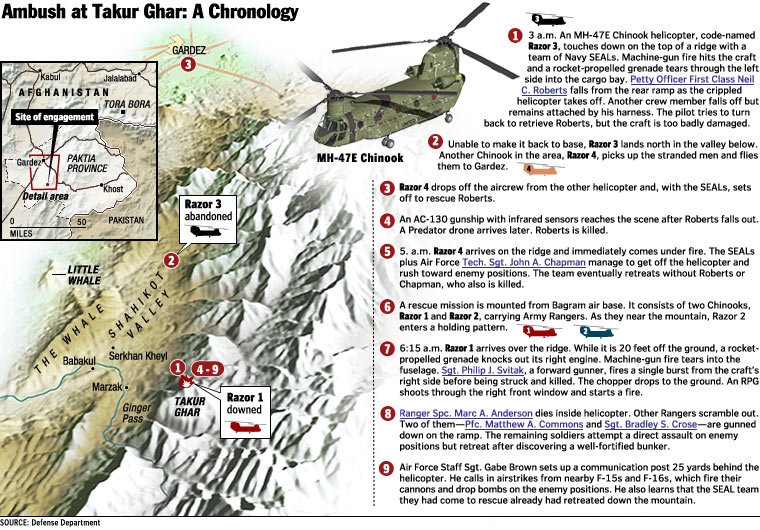

We then move forward a few months, into Operation Anaconda- or more specifically the brief mountain top Battle of Takur Ghar- the infamous assault on the Taliban in the Shahi-Kot valley. Here the developers have taken known elements- special forces teams being dropped into hot LZs, teams being split up, downed transport helicopters, and spritzed the whole up with an archetypal 'idiot boss' general back in the the US (though not in uniform, and not in Washington apparently). This is probably the account of the operation that most people will have seen- 5 million copies of this game have been sold. Many more than would have read an in depth report of the battle, or watched in full any of the news reports (which at the time omitted many of the details for operational security reasons, and probably more than a little embarrassment on the part of the Nato forces). So, when we see US forces subduing a goat-herd by rendering him unconscious, it is in contrast to the reports that US forces criticised German special forces for not killing such by standers. The developers have civilised the US forces. And when the Apaches level a village (a LOT of fun it has to be said) we are told there are no civilians there at all, again in contrast to reported actuality.

|

| An infographic from the Washington Post describing the core actual events upon which the game's story is based. |

This is bowlderised Hollywood historical revisionism of a peculiarly insidious kind. Perhaps. The US is seen as being the sole protagonist nation (UK, Australian, Norwegian, & German forces who are a critical part of the historical event are completely airbrushed out). US forces are shown to treat civilians dubiously, but not murderously as the historical record suggests. Mistakes in planning and deployment are scapegoated onto a single distant general, rather than being the result of complex institutional failures. And the tragedy of lone soldiers and operators being abandoned on mountainsides to be killed alone is replaced by a heroic, if ultimately [SPOILERS!] tale of teams sticking together through thick and thin.

It is just a game, and as I have said early, a pretty good one at that. But this is 'popular history' now. This is the 'Longest Day' of our age, the 'Bridge Over the River Kwai' of the Afghan War. We're seeing a few books, but this, to US eyes at least, second division scrap isn't even getting the meager cultural sifting that that war received. It's a dark and shadowed war, and if this is the only light cast on it, then I fear for history today.

Monday, September 12, 2011

Purdah/ Quarantine

In one week I shall be going under the knife for my long awaited, slightly scarey, very much needed neck operation. In the run up I have decided to cut myself off from external contact as much as possible, because this is that time of year when viral loads go through the roof, populations of infections mingle and swarm, and children go back to school. The phenomena are not unrelated.

Therefore, I'm not taking visitors until after the op, and if you're seeing someone who you think might be seeing me soon, please try not to give them a cold. Ta.

My brother sneezing (sorry Eddie!)

Therefore, I'm not taking visitors until after the op, and if you're seeing someone who you think might be seeing me soon, please try not to give them a cold. Ta.

My brother sneezing (sorry Eddie!)

Sunday, September 11, 2011

Mini Maker Faire Brighton from a Distance

A week and 25 miles, both sufficient to offer some perspective and scintillating parallax but not so far as to obscure utterly in a haze over the horizon. A week ago Brighton held its first fabulous Mini Maker Faire on the opening weekend of the Brighton Digital Festival. The Festival rolls on,right now the Brighton Bar Camp is in full swing- or more likely a mildly jaded gentle start to a Sunday, but there's already an opportunity for us to stand back and look at the effort, the impact of the Maker Faire, and begin to consider what we can do next year.

So, I'll warrant you are pondering, how did it go? I wasn't there. Hence the 25 miles reference. I was in Eastbourne, for reasons and excuses I have outlined earlier. However, 5463 people did make it, an amazing number, far beyond what we'd hoped for. With the greatest thanks to our lovely hosts at the Brighton Dome, who provided the venue for free (I know!), we have to admit that we pushed the space and the aircon to the absolute limit and beyond. From feedback we know a lot of visitors had a hard time getting around to see everything, and that some of the exhibitors came close to melting in the heat- huge thanks to Simon Smith for last minute volunteering and running around quenching collosal thirsts!

So what did I miss, bar heat exhaustion? About 30 exhibitors had come from all points of the compass; Nottingham & Manchester hack space teams made particularly excellent group contributions, but to be honest there was just too much to mention, especially from afar, and besides, Andy Piper has done a fantastic write up of the day that covers it all much better than I could. Because I wasn't there.

The brilliant Tim trying out Project-a-Sketch by Hacman : Video by Elsmorian

One factor that I think is well worth pointing out is that although we were very much a part of the Digital Festival calendar, and the Maker community does have a strong strand of computing based creativity which was on display at the faire, the craft community made a key contribution to the vitality and atmosphere of the day. It's a peculiar point I'm tucking away here in the depths of the post, but this hands on making of beautiful things through traditional and non-traditional crafts is an open engaging and accessible activity- a sharing and non-exclusive thing in the norse sense. I loved the Kinetica Art Fair, but it's undeniable that the conceptual framework of art as displayed there was a barrier to engagement in the physical fabrication of items and the intellectual engagement of the audience as fellow creators. In comparison to the enagaging, teaching, sharing and energising power of craft, art in the formal institutional tradition is stultifying, pacifying, and oppressively exclusive, without in any way being a more creative or meaningful enterprise. I'm putting this very badly, and I do appreciate good art history (I could watch Andrew Graham-Dixon talk about anything!) but art today has put a wall around itself that physically repels much of society, and that makes people, lots of people, feel that they are not creative.

Anyway Charlotte Young puts this a lot better than I can (maybe I go a wee bit further) and she did so at Ignite London where I was deeply privileged to share a platform with her and many other far cleverer people than I.

Art Bollocks (or Stupid Kunst) - by Charlotte Young from chichard41 on Vimeo.

Time to take a break. I shall blog more shortly. Adieu.

Setting up- by Barnoid

So, I'll warrant you are pondering, how did it go? I wasn't there. Hence the 25 miles reference. I was in Eastbourne, for reasons and excuses I have outlined earlier. However, 5463 people did make it, an amazing number, far beyond what we'd hoped for. With the greatest thanks to our lovely hosts at the Brighton Dome, who provided the venue for free (I know!), we have to admit that we pushed the space and the aircon to the absolute limit and beyond. From feedback we know a lot of visitors had a hard time getting around to see everything, and that some of the exhibitors came close to melting in the heat- huge thanks to Simon Smith for last minute volunteering and running around quenching collosal thirsts!

Simonsmithster on hydration duty: photo by Rainrabbit

So what did I miss, bar heat exhaustion? About 30 exhibitors had come from all points of the compass; Nottingham & Manchester hack space teams made particularly excellent group contributions, but to be honest there was just too much to mention, especially from afar, and besides, Andy Piper has done a fantastic write up of the day that covers it all much better than I could. Because I wasn't there.

The brilliant Tim trying out Project-a-Sketch by Hacman : Video by Elsmorian

One factor that I think is well worth pointing out is that although we were very much a part of the Digital Festival calendar, and the Maker community does have a strong strand of computing based creativity which was on display at the faire, the craft community made a key contribution to the vitality and atmosphere of the day. It's a peculiar point I'm tucking away here in the depths of the post, but this hands on making of beautiful things through traditional and non-traditional crafts is an open engaging and accessible activity- a sharing and non-exclusive thing in the norse sense. I loved the Kinetica Art Fair, but it's undeniable that the conceptual framework of art as displayed there was a barrier to engagement in the physical fabrication of items and the intellectual engagement of the audience as fellow creators. In comparison to the enagaging, teaching, sharing and energising power of craft, art in the formal institutional tradition is stultifying, pacifying, and oppressively exclusive, without in any way being a more creative or meaningful enterprise. I'm putting this very badly, and I do appreciate good art history (I could watch Andrew Graham-Dixon talk about anything!) but art today has put a wall around itself that physically repels much of society, and that makes people, lots of people, feel that they are not creative.

Anyway Charlotte Young puts this a lot better than I can (maybe I go a wee bit further) and she did so at Ignite London where I was deeply privileged to share a platform with her and many other far cleverer people than I.

Art Bollocks (or Stupid Kunst) - by Charlotte Young from chichard41 on Vimeo.

Time to take a break. I shall blog more shortly. Adieu.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)